Now that the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics have come to a close, what will it be remembered for? It can’t be the One that happened during a pandemic – the Antwerp 1920 Olympics were held only a few months after the emergence of the Spanish flu. It can’t be the One that happened during a Cold War – the 1980 Games in Moscow takes that title. It can’t even really be remembered as the One that, well, happened – actually, the very first Olympic Games famously wins there. And with no spectators allowed, it’s harder to get the gold for happening – ‘tree falling in the woods’ and all.

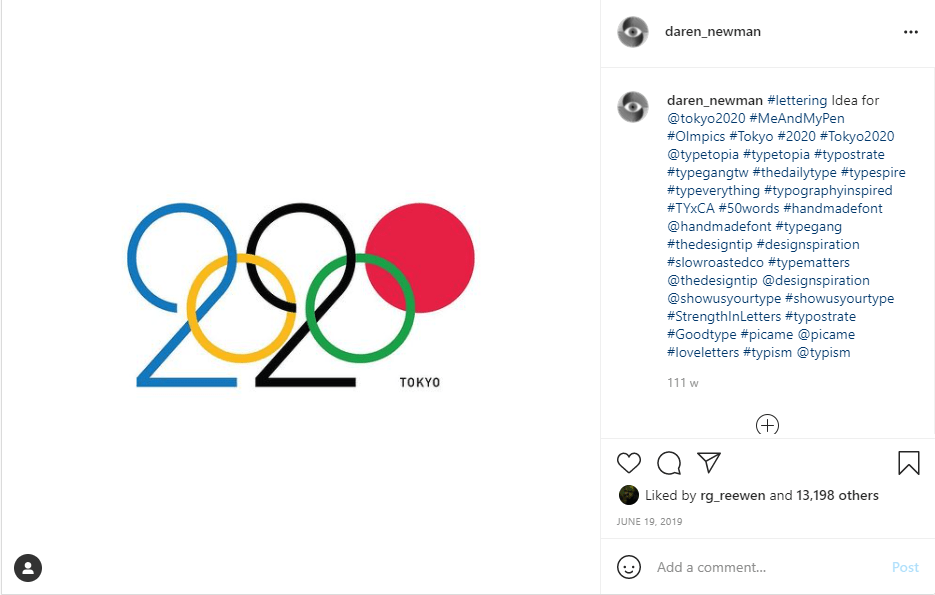

Although postponed for one year, the 2020 Olympics managed to kick off on the 21st of July, 2021. A part of me thinks that the IOC/Tokyo kept the year to keep the most perfect Olympic logo designed by Daren Newman (below). But postponing a game proved to be the forced route over the public-preferred cancellation.

In the lead up to the Opening Ceremony, the Japanese public were not reticent on their feelings for their country hosting (for the fourth time). The Asahi Shimbun reported that 83% of voters said the Tokyo Olympics should be postponed or scrapped1. Protests were frequent2. It seemed that the widely held popular opinion was that Olympics during a time of Global Pandemic was not a very prudent decision.

But, somewhat unsurprisingly, the IOC pushed forward, even acknowledging the ‘erosion of support’ but also said that they would not be guided by public opinion. Even though public opinion is a factor considered in the bid for hosting the Olympics in the first place.

There are strictly limited circumstances that a host country can decide to cancel the Olympics – in fact, the power of cancellation actually is tied solely to the IOC’s discretion3. Clause 66 of a standard Olympic contract contains all the powers the IOC has to terminate; even Japan declaring a state of emergency was not enough to can the Games.

The cult of effort combined with the cult of eurythmy produces an odd form of muscular Christianity; but the contemporary politics of the Olympics can not be understated. As an aside, the ardency of maintaining its ‘apolitical’ status is so crafted to the degree that the Games are, in fact, political.

This blog series aims to have three posts, exploring political situations and contexts that the past 2020 Summer Games have highlighted: firstly, we start off light-hearted looking at the gaffs of exclusive broadcasting. A special nod to the Korean broadcaster MBC here. Next, a look to the impact of international recognition over-riding supposed collective identity (or otherwise tacit agreements) in the Hong Kong case. Winning the first gold as Hong Kong (after the British handover) certainly boosted patriotism for localists; perhaps it too emphasised it’s case for independence? Thirdly, as with any Games, the potential of developing soft power is the peak attraction for a host nation. With no spectators, and a mildly mannered Opening Ceremony (apropos of the country’s Article 9-embedded national characteristic), how did Japan fare in it’s undertaking? This closing post also looks forward to Beijing’s hosting of the forthcoming 2022 Winter Olympics (monikered by some as the ‘Genocide Games’).

Sorry I don’t plan on doing five posts for the five rings. But I’ll make sure to wait four years between posts.

Notes:

- The Asahi Shimbun (2021) ‘Survey: 83% against holding the Tokyo Olympics this summer’ <https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14351670>.

- Wilson, M. (2021) ‘Anger in Tokyo over the Summer Olympics is just the latest example of how unpopular hosting the games has become’ The Conversation <https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14351670>.

- Anderson, J. (2021) ‘Can the Olympics still be cancelled? Yes, but the legal and financial fallout would be stagerring’ The Conversation <https://theconversation.com/can-the-olympics-still-be-cancelled-yes-but-the-legal-and-financial-fallout-would-be-staggering-161739>.